In Linux, the ‘cd‘ (Change Directory) command serves as a fundamental navigation tool for both newcomers and experienced system administrators.

For administrators working on headless servers, ‘cd‘ represents the primary method for traversing the filesystem to examine logs, execute programs, or perform routine tasks. For those new to Linux, it stands among the initial commands they encounter during their learning process.

The command operates through dynamic linking, which allows it to interact directly with the shell’s directory management functions. Since ‘cd‘ is a shell built-in rather than an external binary, it executes with minimal overhead and requires no special privileges beyond standard directory access permissions.

This updated article goes beyond cd and introduces:

pushdandpopd→ for fast directory switching.zoxide→ a modern auto-jump tool that learns your habits.

This creates a complete navigation toolkit for beginners, power-users, and administrators.

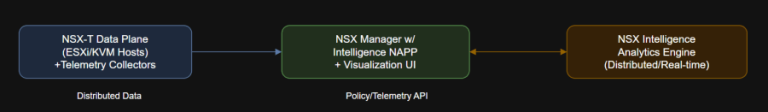

Understanding How cd Command Works

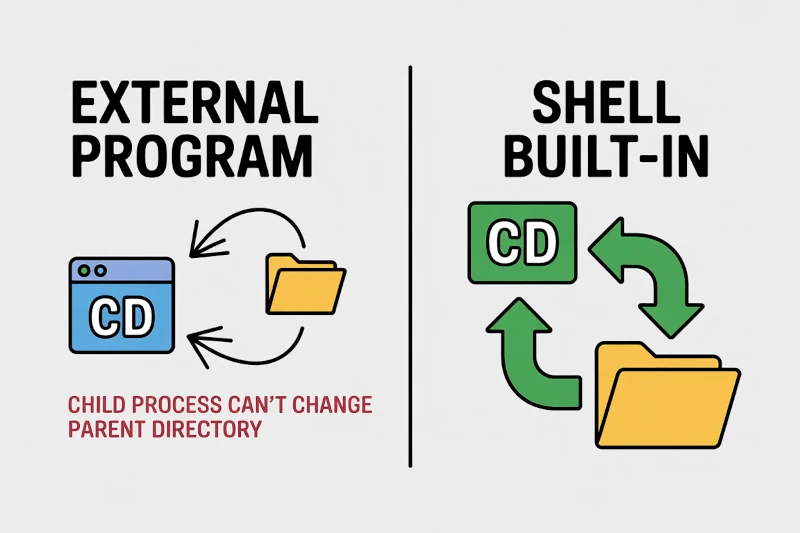

Most commands in Linux you run are actual programs stored in places like /usr/bin or /bin, but cd isn’t one of those, it’s a shell built-in, which means the command lives inside the shell itself.

Why is that important?, because only the shell can change its own working directory. If cd were an external program, it would run as a child process, and child processes aren’t allowed to modify the parent shell’s directory.

So even if it tried to switch folders, nothing would happen when it exited. Being built-in, cd can instantly update your current location in the filesystem without launching anything else.

That’s why it feels so fast and a bit “special” compared to typical commands; it doesn’t load a separate binary, doesn’t create a new process, and requires no special permissions beyond whatever access the directory already allows.

1. Navigating to an Absolute Path

When you want to jump straight to a specific location in the filesystem, no matter where you currently are, you use an absolute path, which always starts with /, which represents the root of the Linux filesystem.

So if you run:

cd /usr/local

you’re telling the shell, “Take me directly to this exact directory”, your current location doesn’t matter. Whether you’re in your home folder, buried deep in a project, or somewhere completely different, an absolute path acts like a GPS route that never changes.

After running the command, your prompt updates to show you’re now inside /usr/local, confirming the jump was successful.

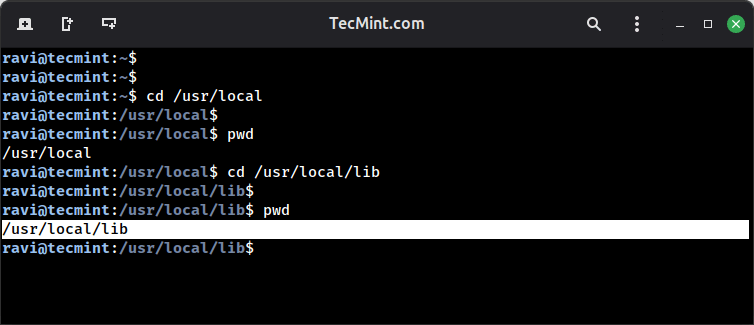

2. Changing to a Subdirectory Using an Absolute Path

You can also use an absolute path when you want to jump directly into a deeper directory. For example, if you’re already in /usr/local and you want to move into its lib folder, you can still type the full path:

cd /usr/local/lib

Even though you’re already halfway there, the shell doesn’t mind, an absolute path always starts at the root / and leads you straight to the final destination, which makes it predictable and reliable, especially when you’re scripting or copying commands from documentation.

After running it, your prompt updates to show that you’re now inside /usr/local/lib, meaning the navigation worked exactly as expected.

3. Navigating Using a Relative Path

When you’re already inside a directory and want to move into one of its subfolders, you don’t need the full path, you can just use a relative path.

For example, if you’re in /usr/local and want to go into the lib directory right beneath it, you can simply run:

cd lib

Since lib exists inside your current directory, the shell knows exactly where to go without needing the entire /usr/local/lib path. Relative paths keep things quick and tidy, especially when you’re working within a specific area of the filesystem.

After the command runs, your prompt updates to show you’re now inside /usr/local/lib, confirming the move.

4. Returning to a Previous or Parent Directory

Sometimes you need to jump back to where you just were, and the quickest way to do that is with the dash operator (-).

cd -

The shell instantly switches you back to your previous working directory and even prints its path so you know exactly where you landed. It’s basically the “back” button of the terminal.

Another common move is going up one level in the directory tree using the double-dot notation (..):

cd ..

This tells the shell, “take me to the parent directory”, so if you’re sitting in /usr/local/lib, running cd .. moves you right back to /usr/local, which is simple, fast, and one of the commands you’ll use constantly while navigating Linux.

5. Displaying the Previous Working Directory

There’s also a way to view the directory you were in before your current one. Using the cd -- form tells the shell to treat everything after it as a plain argument rather than an option, and in this context it outputs the last directory you came from:

cd --

This is useful when you want a quick reminder of where you were working, especially if you’ve been jumping around multiple paths and lost track. It doesn’t move you anywhere, it simply shows the previous location, giving you a quick reference point without changing your current directory.

6. Traversing Multiple Directory Levels

You’re not limited to moving up just one level, you can jump through several layers at once using multiple .. segments and each .. represents “go to the parent directory” and you can chain them together.

For example, if you’re currently in /usr/local and want to move up two levels, you can run:

cd ../../

The first .. takes you from local to usr, and the second one moves you from usr to the root directory’s next level up—landing you in /usr.

7. Navigating to Your Home Directory

No matter where you are in the filesystem, getting back to your home directory is easy, just use the tilde (~), which is a shortcut that always represents your home location.

cd ~

instantly drops you back into your personal workspace and there’s an even simpler trick: if you type cd with no arguments at all, the shell assumes you want to return home and takes you there automatically:

cd

Both commands lead to the exact same place, making it quick and effortless to jump back to familiar ground from anywhere in the system.

8. Staying in the Current Directory

The . symbol represents your current directory, so running cd . doesn’t actually move you anywhere, it simply tells the shell to “go to the place you’re already in”, it’s technically a valid command, but it produces no meaningful change:

cd .

You’ll notice your prompt stays exactly the same and the same thing happens if you add a trailing slash:

cd ./

Both versions point right back to your current location. While it’s not something you’ll use often, it’s helpful to understand because the . notation appears frequently in scripts and file paths.

9. Navigating Through Multiple Directory Levels

When you’re buried deep inside a long directory path, you can climb all the way out and jump to a completely different location using a mix of .. steps and a full path and each .. moves you up one level, so chaining them lets you backtrack through several folders in one go.

For example, if you’re stuck in a long directory like:

/usr/local/lib/python3.4/dist-packages/

you can move all the way back toward the root and then point directly to your target:

cd ../../../../../home/avi/Desktop/

The series of .. segments walks you up through each parent directory, and once you’ve climbed high enough, the absolute path that follows takes you straight to your Desktop.

10. Using Tab Completion for Faster Path Navigation

One of the easiest ways to save time in the terminal is by using Tab completion. Instead of typing long directory names manually, you can type just the first few letters and press TAB, and the shell will auto-complete the rest for you.

For example, to reach /var/www/html, you don’t need to type out the whole path:

cd /v<TAB>/w<TAB>/h<TAB>

Each time you hit TAB, the shell fills in the matching directory name /var, then /www, then /html. This not only speeds up your navigation, but also reduces typos and helps you discover available directories as you go.

Once the path is complete, pressing Enter takes you straight into /var/www/html.

11. Navigating Using Wildcards

When you can’t remember the full name of a directory and TAB completion isn’t helping, you can use wildcards to fill in the gaps. The * symbol acts like a placeholder that matches anything, so if you know a directory in /etc/ starts with the letter v, you can try:

cd /etc/v*

The shell looks for directories beginning with v and completes the path using the first match it finds. If only one directory fits, you’ll land in it immediately like jumping straight into /etc/vbox.

Just keep in mind: this works smoothly only when a single match exists. If multiple directories start with v, the shell will pick the first one in alphabetical order, which might not be the one you intended.

Still, wildcard navigation can be a handy shortcut when your memory is fuzzy and you need a quick way to move around.

12. Using Single-Character Wildcards

Sometimes you remember most of a directory name but not the entire thing. In cases like that, you can use the single-character wildcard: the question mark (?). Unlike the asterisk, which matches any number of characters, ? matches exactly one.

So if you know your home directory starts with av but you’re unsure about the last character, you can run:

cd /home/av?

The shell will look for any directory in /home/ that starts with av and has one more character after it. If there’s a match, it will take you right there, like landing in your home directory /home/avi.

13. Managing Directories with pushd and popd

While cd is great for basic navigation, sometimes you need a quicker way to jump between two or more directories without losing your place. That’s where pushd and popd come in. They work like a “directory stack” – a small memory list that stores locations you’ve visited.

When you use pushd, the shell saves your current directory on the stack and then moves you to the new one:

pushd /var/www/html

After running it, your shell shows both the new directory and the one saved on the stack. Now you can work inside /var/www/html without worrying about how to get back.

When you’re ready to return, just use popd:

popd

This pulls the previously saved directory off the stack and drops you right back into it. It’s a super convenient way to bounce between paths, perfect for multitasking, editing files in different locations, or switching back and forth during development work.

14. Handling Directories with Spaces

Directories with spaces in their names can be tricky in the terminal because the shell normally treats spaces as separators, but you’ve got a few easy ways to navigate into them.

The first option is to escape the space with a backslash:

cd test tecmint/

Another method is to wrap the entire directory name in single quotes:

cd 'test tecmint'

Or you can use double quotes, which work the same way for simple directory names:

cd "test tecmint"/

Any of these approaches will get you into directories that contain spaces, so use whichever one feels most natural to you, quotes tend to be the quickest and easiest.

15. Chaining Commands After a Directory Change

Sometimes you want to change directories and immediately run another command, without typing two separate lines. That’s where the logical AND operator (&&) comes in handy.

It lets you chain commands together so the second one only runs if the first one succeeds. For example, if you want to jump into your Downloads folder and instantly list everything inside it, you can do:

cd ~/Downloads && ls

The cd command moves you into the directory, and only if that works, ls command runs and shows the files inside.

BONUS: Supercharge Your Navigation with zoxide (Highly Recommended)

If you want to take directory navigation to the next level, zoxide is faster version of cd that learns where you like to go. It uses a “frecency” algorithm, meaning it tracks how frequently and recently you visit directories.

Installing it is easy (here’s the Ubuntu example):

sudo apt install zoxide eval "$(zoxide init bash)"

Once it’s set up, you can jump to directories using only tiny fragments of their names, which takes you to whichever directory named “project” (or similar) you visit the most.

z proj

Want to jump into log folders you use all the time?

z logs

Conclusion

The cd command is more than just a basic navigation tool, it’s a built-in part of the shell itself. Because it runs inside the current shell process, it can change your working directory instantly without launching a separate program.

Once you understand how cd works and how to combine it with shortcuts, relative paths, wildcards, directory stacks, and tools like zoxide – moving around the filesystem becomes much faster and far more efficient.

These techniques cut down on typing, speed up your workflow, and make everyday terminal work feel smoother, whether you’re learning Linux for the first time or managing servers like a pro